Introduction to Unix #

Unix is a family of operating systems featuring a similar API and design, including Unix, BSD, Solaris and Linux.

Some Unix characteristics that are at the core of its strength:

- Unix is simple: only hundreds of system calls and have a straightforward, even basic, design.

- In Unix, everything is a file: simplifies the manipulation of data and devices into a set of core system calls: open(),read(), write(), lseek(), and close().

- Unix has robust IPC (Interprocess communication) systems.

Overview of Operating Systems and Kernels #

The operating system is the parts of the system responsible for basic use and administration. The kernel is the innermost portion of the operating system. It is the core internals: the software that provides basic services for all other parts of the system, manages hardware, and distributes system resource.

An OS contains:

- Kernel:

- Interrupt handlers to service interrupt requests.

- A scheduler to share processor time among multiple processes.

- A memory management system to manage process address spaces.

- System services such as networking and interprocess communication.

- Device drivers

- Boot loader

- Command shell

- User interfaces

- Basic utilities

Kernel-space and User-space #

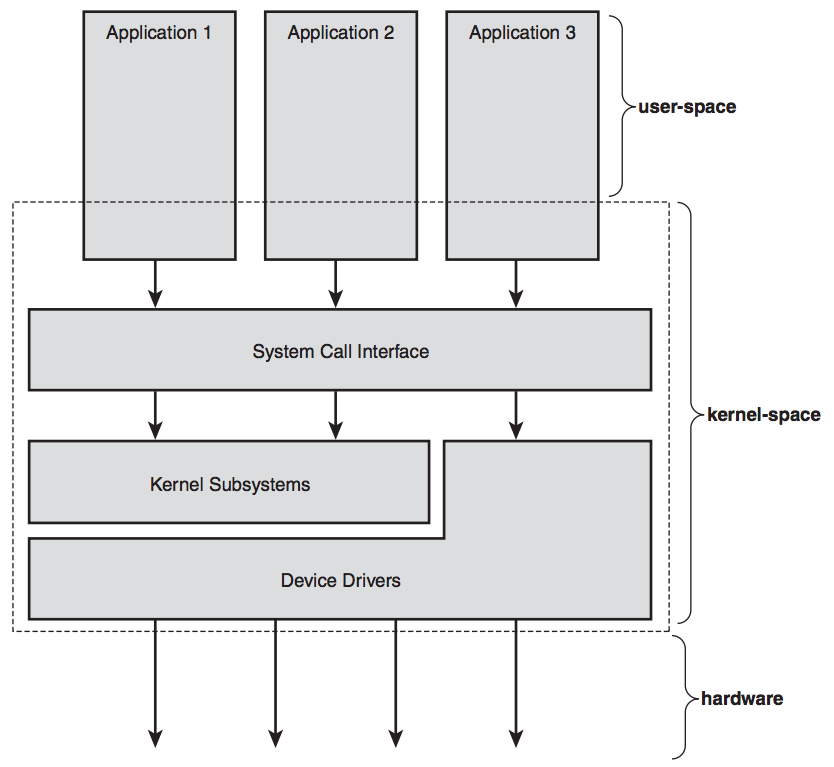

Kernel-space: on modern systems with protected memory management units, the kernel typically resides in an elevated system state, which includes a protected memory space and full access to the hardware. This system state and memory space is collectively referred to as kernel-space.

User-space: applications execute in user-space, where they can access a subset of the machine’s available resources and can perform certain system functions, directly access hardware, access memory outside of that allotted them by the kernel, or otherwise misbehave.

When executing kernel code, the system is in kernel-space executing in kernel mode. When running a regular process, the system is in user-space executing in user mode.

Applications running on the system comminicate with the kernel using system calls (Figure 1.1)

Basically, an application will use a C library to use the system call interface. The system calls will allow the Kernel to do operation on behalf of the application. Furthermore, the application is said to be executing a system call in kernel-space, and the kernel is running in process context.

Some function of this C library provide many feature not found in system calls, E.G. the printf() function will not only wall the write() system call but will also do formating, etc…

On the other hand, the open() function simply use the open() system call. Other functions of this C library does not use system calls at all, E.G. strcpy().

The Kernel also manage system’s hardware. When the hardware want to communicate, it will send an hardware interrupt to the CPU, which will in turn interrupt the Kernel, which will in turn operate a context switch to execute the interrupt handler.

graph LR; A[Hardware] -->|Interrupt lines| B[CPU] B[CPU] -->|Interrupt| C[Kernel] C[Kernel] -->|Interrupt Handler| D[Run the interrupt handler code]

A number identifies each interrupt, the kernel reads this number and then execute the handler code.

For example:

sequenceDiagram participant Y as You participant KC as Keyboard Controller participant C as CPU participant KR as Kernel participant IH as Interrupt Handler Process Y->>KC: Type on keyboard KC->>C: Issue an hardware interrupt C->>KR: Forward interrupt with interrupt number KR->>IH: Run interrupt handler according to interrupt number IH->>KC: Process Keyboard data IH->>KC: Let it know it's ready for more data

Running interrupt handlers put the Kernel in a special context, the interrupt context, not associated with any process.

Each CPU in the Linux Kernel is doing exaclty one of the following:

- In user-space, running user code in a process.

- In kernel-space, in process context, running kernel code on behalf of a specific process.

- In kernel-space, in interrupt context, not associated with any process, handling an interrupt.

This list is inclusive, every cases fit any of the previous element. E.G. Even when the Kernel is idle, the CPU is actually running an idle process

Monolithic Kernels vs Microkernels #

Most Unix kernels are monolithics and although the Linux kernel is monolithic, it can dynamically load and unload kernel modules on demand.

Monolithic Kernels are:

- Simpler than Microkernels.

- Implemented as a single process.

- Exist as a single binary.

- Runs in kernel mode.

- Runs everything in the same address space.

- Because of this, communication is trivial, the kernel simply invoke functions.

Microkernels are:

- Broken down into separate process, called servers

- Only some servers runs in priviledged mode, if they need it, the rest runs in user mode.

- Because of this, direct function invocation is impossible.

- Microkernel uses message passing, an Inter Process communication (IPC) method.

- Servers invoke services from other servers, using message passing.

- Microkernels are modular, if one server crash, it doesn’t crash the all kernel.

- IPC (message passing) and context switches (user mode vs privileged mode) involve some serious overhead

- To avoid this, modern Microkernels (Windows NT and mac OS) runs every servers in privileged mode, defeating the primary purpose of microkernels.