Memory Management #

Unlike user-space, the kernel is not always afforded the capability to easily allocate memory. For example, the kernel cannot easily deal with memory allocation errors, and the kernel often cannot sleep. Because of these limitations, and the need for a lightweight memory allocation scheme, getting hold of memory in the kernel is more complicated than in user-space.

Pages #

The kernel treats physical pages as the basic unit of memory management. Although the processor’s smallest addressable unit is a byte or a word, the memory management unit (MMU, the hardware that manages memory and performs virtual to physical address translations) typically deals in pages. Therefore, the MMU maintains the system’s page tables with page-sized granularity (hence their name). In terms of virtual memory, pages are the smallest unit that matters.

Each architecture defines its own page size. Many architectures even support multiple page sizes.

- Most 32-bit architectures have 4KB pages.

- Most 64-bit architectures have 8KB pages.

The kernel represents every physical page on the system with a struct page structure.

The kernel uses this structure to keep track of all the pages in the system, because the kernel needs to know whether a page is free (whether the page is not allocated).

If a page is not free, the kernel needs to know who owns the page. Possible owners include (but not limited to):

- User-space processes.

- Dynamically allocated kernel data.

- Static kernel code.

- Page cache.

The page structure is associated with physical pages, not virtual pages; what the structure describes is transient at best. Even if the data contained in the page continues to exist, it might not always be associated with the same page structure because of swapping and so on. The kernel uses this data structure to describe the associated physical page. The data structure’s goal is to describe physical memory, not the data contained therein.

Since an instance of this structure is allocated for each physical page in the system, how much space is used to maintain the pages structures?

With each struct page consuming 40 bytes of memory and assuming that the system has 8KB physical pages and has 4GB of physical memory. In that case, there are about 524,288 pages and page structures on the system.

The page structures consume 20MB: perhaps a surprisingly large number in absolute terms, but only a small fraction of a percent relative to the system’s 4GB. This is not too high a cost for managing all the system’s physical pages.

Zones #

The kernel cannot treat all pages as identical due to hardware limitations. Some pages, because of their physical address in memory, cannot be used for certain tasks. Thus, the kernel divides pages into different zones. The kernel uses the zones to group pages of similar properties.

Linux has to deal with two shortcomings of hardware with respect to memory addressing:

- Some hardware devices can perform DMA (direct memory access) to only certain memory addresses.

- Some architectures can physically addressing larger amounts of memory than they can virtually address. Consequently, some memory is not permanently mapped into the kernel address space.

Due to these contraints, Linux has four primary memory zones:

ZONE_DMA: This zone contains pages that can undergo DMA.ZONE_DMA32: LikeZONE_DMA, this zone contains pages that can undergo DMA. UnlikeZONE_DMA, these pages are accessible only by 32-bit devices. On some architectures, this zone is a larger subset of memory.ZONE_NORMAL: This zone contains normal, regularly mapped, pages.ZONE_HIGHMEM: This zone contains “high memory”, which are pages not permanently mapped into the kernel’s address space.

The layout of the memory zones is architecture-dependent.

- Some architectures can perform DMA into any memory address. In those architectures,

ZONE_DMAis empty andZONE_NORMALis used for allocations regardless of their use. - On the x86 architecture, ISA devices cannot perform DMA into the full 32-bit address space because ISA devices can access only the first 16MB of physical memory. Consequently,

ZONE_DMAon x86 consists of all memory in the range 0MB–16MB.

ZONE_HIGHMEM works similarly.

- On 32-bit x86 systems,

ZONE_HIGHMEMis all memory above the physical 896MB mark. On other architectures,ZONE_HIGHMEMis empty because all memory is directly mapped. The memory contained inZONE_HIGHMEMis called high memory. The rest of the system’s memory is called low memory. ZONE_NORMALis the remainder after the previous two zones claim their requisite shares. On x86,ZONE_NORMALis all physical memory from 16MB to 896MB. On other architectures,ZONE_NORMALis all available memory.

The following table is a listing of each zone and its consumed pages on x86-32.

| Zone | Description | Physical Memory |

|---|---|---|

| ZONE_DMA | DMA-able pages | < 16MB |

| ZONE_NORMAL | Normally addressable pages | 16–896MB |

| ZONE_HIGHMEM | Dynamically mapped pages | > 896MB |

Linux partitions pages into zones to have a pooling in place to satisfy allocations as needed.

For example, with a ZONE_DMA pool, the kernel has the capability to satisfy memory allocations needed for DMA.

If such memory is needed, the kernel can simply pull the required number of pages from ZONE_DMA.

The zones do not have any physical relevance but are simply logical groupings used by the kernel to keep track of pages.

Although some allocations may require pages from a particular zone, other allocations may pull from multiple zones. For example:

- An allocation for DMA-able memory must originate from

ZONE_DMA - A normal allocation can come from

ZONE_DMAorZONE_NORMALbut not both; allocations cannot cross zone boundaries. The kernel prefers to satisfy normal allocations from the normal zone to save the pages inZONE_DMAfor allocations that need it.

Not all architectures define all zones. For example, a 64-bit architecture such as Intel’s x86-64 can fully map and handle 64-bits of memory.

Thus, x86-64 has no ZONE_HIGHMEM and all physical memory is contained within ZONE_DMA and ZONE_NORMAL.

Each zone is represented by struct zone structure.

Getting Pages #

The Kernel implement different interfaces to enable memory allocation and release.

The kernel provides one low-level mechanism for managing memory, along with several interfaces to access it. All these interfaces manage memory with page-sized granularity. It is possible for the kernel to provide zeroed pages. This is useful for pages given to userspace because the random garbage in an allocated page is not so random; it might contain sensitive data. All data must be zeroed or otherwise cleaned before it is returned to userspace to ensure system security is not compromised.

These low-level page functions are useful when page-sized chunks of physically contiguous pages are needed, especially if the need is exactly a single page or two. For more general byte-sized allocations, the kernel provides kmalloc().

kmalloc() #

The kmalloc() function is similar to user-space’s malloc(), with the exception of the additional flags parameter. The kmalloc() function is a simple interface for obtaining kernel memory in byte-sized chunks. If whole pages are needed, the previously discussed interfaces might be a better choice. For most kernel allocations, kmalloc() is the preferred interface.

The kmalloc() function returns a pointer to a region of memory that is at least size bytes in length. It may allocate more than asked, although it is not possible to know how much more.

Because the kernel allocator is page-based, some allocations may be rounded up to fit within the available memory.

The kernel never returns less memory than requested. If the kernel is unable to find at least the requested amount, the allocation fails and the function returns NULL.

The region of memory allocated is physically contiguous. Kernel allocations always succeed, unless an insufficient amount of memory is available. Thus, a check for NULL after all calls to kmalloc() and handling the error appropriately should be done.

Flags can be passed as parameters to kmalloc() to modify its behaviour. To specify from which zones to allocate memory for example, by default, it will allocate from either ZONE_DMA or ZONE_NORMAL, with a strong preference to satisfy the allocation from ZONE_NORMAL.

kmalloc() cannot allocate from ZONE_HIGHMEM. Only low-level interfaces can allocate high memory.

kfree() #

The counterpart to kmalloc() is kfree(). It frees a block of memory previously allocated with kmalloc().

Calling this function on memory not previously allocated with kmalloc(), or on memory that has already been freed is a bug, resulting in bad behavior such as freeing memory belonging to another part of the kernel. As in user-space, each allocations should be at some point deallocated to prevent memory leaks and other bugs.

vmalloc() #

The vmalloc() function works in a similar fashion to kmalloc(), except vmalloc() allocates memory that is only virtually contiguous and not necessarily physically contiguous.

This is similar to user-space malloc() and its usage is identical. The returned pages by which are contiguous within the virtual address space, but necessarily contiguous in physical RAM.

The vmalloc() function ensures that the pages are physically contiguous by by allocating potentially noncontiguous chunks of physical memory and “fixing up” the page tables to map the memory into a contiguous chunk of the logical address space.

- Usually, only hardware devices require physically contiguous memory allocations, because they live on the other side of the memory management unit and do not understand virtual addresses.

- Blocks of memory used only by software (e.g.process-related buffers) are fine using memory that is only virtually contiguous. All memory appears to the kernel as logically contiguous.

Though physically contiguous memory is required in only certain cases, most kernel code uses kmalloc() and not vmalloc() to obtain memory primarily for performance.

The vmalloc() function, to make nonphysically contiguous pages contiguous in the virtual address space, must specifically set up the page table entries.

Worse, pages obtained via vmalloc() must be mapped by their individual pages (because they are not physically contiguous), which results in much greater TLB thrashing compared to using directly mapped memory.

Because of these concerns, vmalloc() is used only when absolutely necessary (typically, to obtain large regions of memory). For example, when modules are dynamically inserted into the kernel, they are loaded into memory created via vmalloc().

vfree() is used to free an allocation obtained via vmalloc().

Slab Layer #

Allocating and freeing data structures is one of the most common operations inside any kernel. To facilitate frequent allocations and deallocations of data, programmers often introduce free lists. A free list contains a block of available, already allocated, data structures.

- When code requires a new instance of a data structure, it can grab one of the structures off the free list rather than allocate the sufficient amount of memory and set it up for the data structure.

- When the data structure is no longer needed, it is returned to the free list instead of deallocated. In this sense, the free list acts as an object cache, caching a frequently used type of object.

One of the main problems with free lists in the kernel is that there exists no global control. When available memory is low, there is no way for the kernel to communicate to every free list that it should shrink the sizes of its cache to free up memory. The kernel has no understanding of the random free lists at all. To remedy this, and to consolidate code, the Linux kernel provides the slab layer (also called the slab allocator). The slab layer acts as a generic data structure-caching layer.

The concept of slab layer comes from Sun Microsystem’s SunOS, Linux data structure caching layer shares the same name and basic design.

The slab layer attempts to leverage several basic tenets:

- Frequently used data structures tend to be allocated and freed often, so cache them.

- Frequent allocation and deallocation can result in memory fragmentation (the inability to find large contiguous chunks of available memory). To prevent this, the cached free lists are arranged contiguously. Because freed data structures return to the free list, there is no resulting fragmentation.

- The free list provides improved performance during frequent allocation and deallocation because a freed object can be immediately returned to the next allocation.

- If the allocator is aware of concepts such as object size, page size, and total cache size, it can make more intelligent decisions.

- If part of the cache is made per-processor (separate and unique to each processor on the system), allocations and frees can be performed without an SMP lock.

- If the allocator is NUMA-aware, it can fulfill allocations from the same memory node as the requestor.

- Stored objects can be colored to prevent multiple objects from mapping to the same cache lines.

The slab layer in Linux was designed and implemented with these premises in mind.

Design of the Slab Layer #

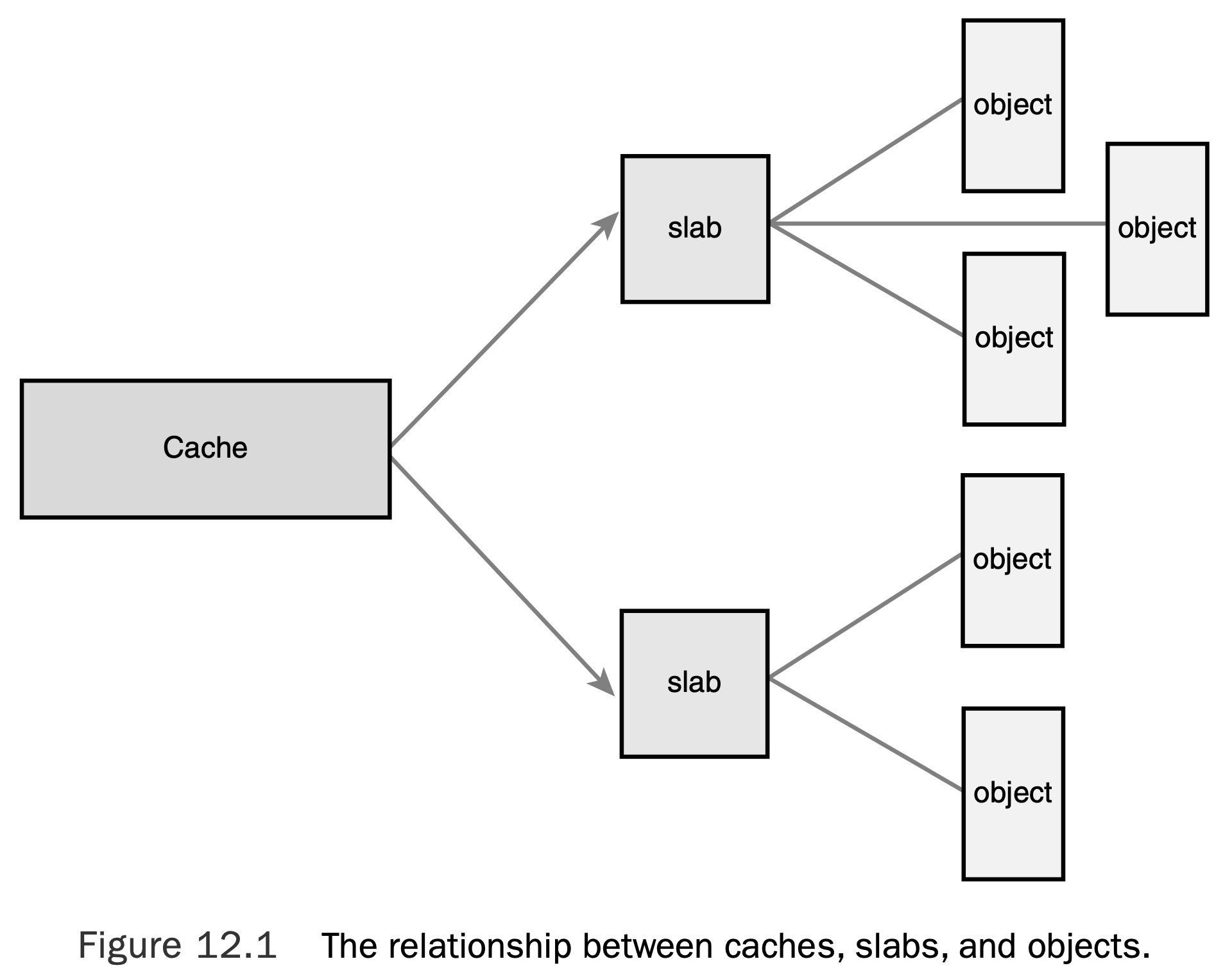

The slab layer divides different objects into groups called caches, each of which stores a different type of object. There is one cache per object type.

For example, one cache is for process descriptors (a free list of task_struct structures), whereas another cache is for inode objects (struct inode).

Interestingly, the kmalloc() interface is built on top of the slab layer, using a family of general purpose caches.

The caches are then divided into slabs (hence the name of this subsystem). The slabs are composed of one or more physically contiguous pages. Typically, slabs are composed of only a single page. Each cache may consist of multiple slabs. Each slab contains some number of objects, which are the data structures being cached.

Each slab is in one of three states:

- A full slab has no free objects. (All objects in the slab are allocated.)

- A partial slab has some allocated objects and some free objects.

- An empty slab has no allocated objects. (All objects in the slab are free.)

When some part of the kernel requests a new object, the request is satisfied from a partial slab, if one exists. Otherwise, the request is satisfied from an empty slab. If there exists no empty slab, one is created. Obviously, a full slab can never satisfy a request because it does not have any free objects. This strategy reduces fragmentation.

Statically Allocating on the Stack #

User-space can afforded large, dynamically growing stack, whereas the the kernel’s stack is small and fixed.

The size of the per-process kernel stacks depends on both the architecture and a compile-time option. Historically, the kernel stack has been two pages per process by default. It is now only one page per process.

This is usually:

- 4KB for 32-bit architectures (with one 4KB page).

- 8KB for 64-bit architectures (wtih one 8KB page).

The move to single-page kernel stacks was done for two reasons:

- It results in a page with less memory consumption per process.

- As uptime increases, it becomes increasingly hard to find two physically contiguous unallocated pages. Physical memory becomes fragmented, and the resulting VM pressure from allocating a single new process is expensive.

There is one more complication. Each process’s entire call chain has to fit in its kernel stack. Historically, however, interrupt handlers also used the kernel stack of the process they interrupted, thus they too had to fit. This was efficient and simple, but it placed even tighter constraints on the already meager kernel stack. When the stack moved to only a single page, interrupt handlers no longer fit.

To rectify this problem, the kernel developers implemented a new feature: interrupt stacks. Interrupt stacks provide a single per-processor stack used for interrupt handlers. With this option, interrupt handlers no longer share the kernel stack of the interrupted process. Instead, they use their own stacks. This consumes only a single page per processor.

To summarize, kernel stacks are either one or two pages, depending on compile-time configuration options. The stack can therefore range from 4KB to 16KB. Historically, interrupt handlers shared the stack of the interrupted process. When single page stacks are enabled, interrupt handlers are given their own stacks.

Playing Fair on the Stack #

In any given function, stack usage should be kept to a minimum. The sum of all local (automatic) variables in a function should be kept to a maximum of a couple hundred bytes. Performing a large static allocation on the stack (e.g. a large array or structure) is dangerous. Otherwise, stack allocations are performed in the kernel just as in user-space.

Stack overflows occur silently and will undoubtedly result in problems. Because the kernel does not make any effort to manage the stack, when the stack overflows, the excess data simply spills into whatever exists at the tail end of the stack, the first thing of which is the thread_info structure, which is allocated at the end of each process’s kernel stack.

Beyond the stack, any kernel data might lurk. At best, the machine will crash when the stack overflows. At worst, the overflow will silently corrupt data. Therefore, it is wise to use a dynamic allocation scheme for any large memory allocations.

High Memory Mappings #

By definition, pages in high memory might not be permanently mapped into the kernel’s (virtual) address space. Thus, pages obtained via alloc_pages() with the __GFP_HIGHMEM flag might not have a logical address.

On the x86 architecture, all physical memory beyond the 896MB mark is high memory and is not permanently or automatically mapped into the kernel’s address space, despite x86 processors being capable of physically addressing up to 4GB (64GB with PAE) of physical RAM.

After they are allocated, these pages must be mapped into the kernel’s logical address space. On x86, pages in high memory are mapped somewhere between the 3GB and 4GB mark.

Permanent Mappings #

To map and unmap a given page structure into the kernel’s address space, the kmap() and kunmap() functions can be used.

These functions works on either high or low memory and they can sleep.

When mapping:

- If the page structure belongs to a page in low memory, the page’s virtual address is simply returned.

- If the page resides in high memory, a permanent mapping is created and the address is returned.

Because the number of permanent mappings are limited, high memory should be unmapped when no longer needed.

Temporary Mappings #

When a mapping must be created but the current context cannot sleep, the kernel provides temporary mappings (also called atomic mappings). The kernel can atomically map a high memory page into one of the reserved mappings (which can hold temporary mappings). Consequently, a temporary mapping can be used in places that cannot sleep, such as interrupt handlers, because obtaining the mapping never blocks.

Setting up and tearing down a temporary mapping is done via kmap_atomic() and kunmap_atomic().

This function does not block and thus can be used in interrupt context and other places that cannot reschedule. It also disables kernel preemption, which is needed because the mappings are unique to each processor and a reschedule might change which task is running on which processor.

In many architectures, unmapping does not do anything at all except enable kernel preemption, because a temporary mapping is valid only until the next temporary mapping. Thus, the kernel can just “forget about” the temporary mapping. The next atomic mapping then simply overwrites the previous one.