The Process #

A process, or task in the Kernel, is a program (object code) that is currently running, but a program is not a process, two or more processes can actually run the same program at the same time.

They are more than juste code (text section), they also include a set of resources such as:

- Open files.

- Pending signals.

- Internal Kernel data.

- Processor state.

- A memory address space with one or more mappings.

- One or more threads of execution.

- A data section containing global variables.

Threads of execution, or threads, are the objects of activity within the process. Each thread includes:

- A unique program counter.

- A Process stack.

- A set of processor registers.

The kernel schedules individual threads, not processes.

Process that runs more than one thread are call multithreaded.

On modern operating systems, processes provide two virtualizations:

- A virtualized processor: The virtual processor gives the process the illusion that it alone monopolizes the system, despite possibly sharing the processor among hundreds of other processes.

- A virtual memory: Virtual memory lets the process allocate and manage memory as if it alone owned all the memory in the system.

Note that threads share the virtual memory abstraction, but they each receives their own virtualized processor.

Process lifecycle #

The process lifecycle goes as follow:

- fork(): A parent process will run the fork() system call, effectively cloning himself (fork() is implemented using clone()) into a child process. The parent process will then resume execution and the child process will start execution at the same place, where the fork() system call returns. fork() will in fact return twice, once in the parent process, and once in the child process. At some point however, the parent process will have to run a wait() type system call to reap its exited child process.

- exec(): After its creation, the child process will run one of the exec() system calls that will create a new address space and load a new program into it.

- exit(): Finally, when a process exits, it run the exit() system call. This will terminate the process and free all its ressources. The process will then be placed in a zombie state and until its parent process run the wait4() system call.

Process Descriptor and the Task Structure #

The kernel stores the list of processes in a circular doubly linked list called the task list. Each element of this list is called a process descriptor that will contain all informations about a given process.

The system identifies processes by a unique process identification value or PID, stored in the process descriptor. The PID is typically an integer going up to 32,768. This maximum value is important because it is essentially the maximum number of processes that may exist concurrently on the system.

The Kernel will affect PID to each process in an ascending order, this creates the notion that the higher the PID, the later the process started. But if the maximum number of PID is reached, then it will wrap back and try to affect freed PID to new process, detroying this useful notion.

You can also increase this value up to four millons, by modifying /proc/sys/kernel/pid_max. Take note that this might break compatibility with older programs.

Process State #

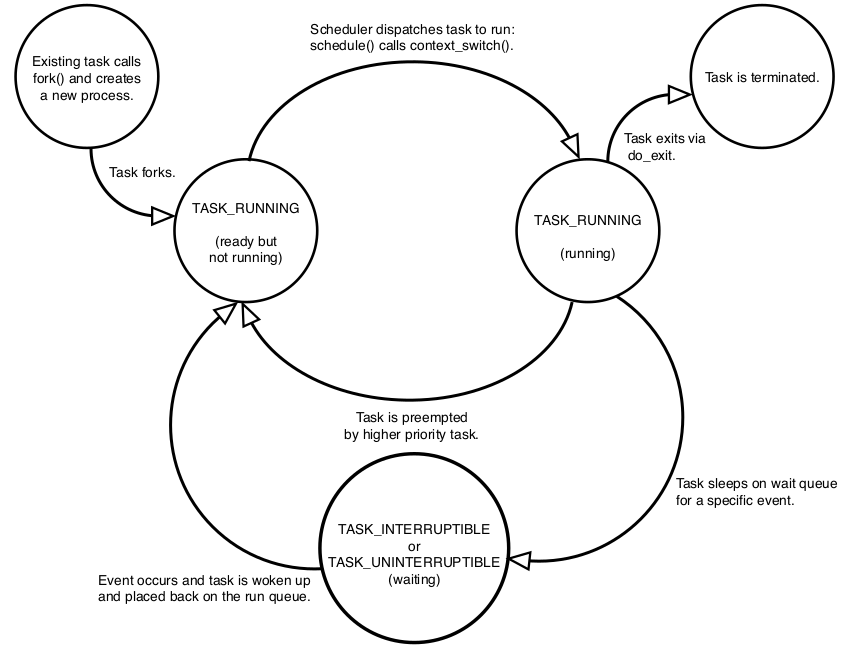

The state field of the process descriptor describes the current condition of the process. Each process on the system is in exactly one of the five following states:

- TASK_RUNNING: The process is runnable, it is either currently running or on a runqueue waiting to run. This is the only possible state for a process executing in user-space. It can also apply to a process in kernel-space that is actively running.

- TASK_INTERRUPTIBLE: The process is sleeping, or blocked, waiting for some condition to exist. When this condition exists, the kernel sets the process’s state to TASK_RUNNING. The process also awakes prematurely and becomes runnable if it receives a signal.

- TASK_UNINTERRUPTIBLE: This state is identical to TASK_INTERRUPTIBLE except that it does not wake up and become runnable if it receives a signal. This is used in situations where the process must wait without interruption or when the event is expected to occur quite quickly. Because the task does not respond to signals in this state, TASK_UNINTERRUPTIBLE is less often used than TASK_INTERRUPTIBLE.

- __TASK_TRACED: The process is being traced by another process, such as a debugger (like strace), using the ptrace() system call.

- __TASK_STOPPED: Process execution has stopped. The task is not running nor is it eligible to run. This occurs if the task receives the SIGSTOP, SIGTSTP, SIGTTIN, or SIGTTOU signal or if it receives any signal while it is being debugged.

Take note that a process in the TASK_UNINTERRUPTIBLE state will not even respond to SIGKILL. This state is represented by the famous D state in the ps command.

Process Context #

The goal of a process is to execute program code. This code is read from an executable file and executed from within the program’s address space. Normal program execution occurs in user-space, when a program executes a system call or triggers an exception, it enters kernel-space. At this point, the kernel is said to be “executing on behalf of the process” and the kernel is in process context.

Upon exiting the kernel, the process resumes execution in user-space, unless a higher-priority process has become runnable in the interim, in which case the scheduler is invoked to select the higher priority process.

System calls and exception handlers are well-defined interfaces into the kernel. A process can begin executing in kernel-space only through one of these interfaces. All access to the kernel is through these interfaces.

The Process Family Tree #

There is a hierarchy between processes. All processes are descendant of the init process, whose PID is 1. The Kernel will start the init process as the last step of the boot procedure. The init process will then read the initscripts and start all other programs necessary to complete the boot procedure.

Every process on the system has exactly one parent. Likewise, every process has zero or more children. Processes that are all direct children of the same parent are called siblings.

Process Creation #

Process creation in Unix is unique. Unix takes the unusual approach of separating these steps into two distinct system calls: fork() and exec().

- fork() will create a child process that is a copy of the current task. It only differs by its PID, PPID (Parent PID) and some other resources, such as pending signals which are not inherited.

- exec() will load a new program in the task address space and start executing it.

Copy-on-Write #

Traditionnaly, upon fork(), all resources owned by the parent process are copied to the child process memory space. Even worse, if the first call of the child process is exec(), then all the copied data is discarded to allow the new program to run. To optimize this, Linux’s fork() is using what is called copy-on-write pages.

Copy-on-write, or COW is working like this:

- When the fork() system call is invoked, rather than duplicating the address space, each process, parent and child, will share a single read-only copy.

- The data is marked so that if it is written to, a duplicate is made and each process will get its own copy, therefor, copy-on-write. Only the pages that are written to are duplicated, the rest of the memory space will still be shared.

If the pages are never written, for example if the child calls exec() directly after the fork(), then the pages are never copied. To make sure that the child process is given the possibility to run exec() before the parent write to the data, the Kernel will schedule first the child process.

Threads #

Thread provide multiple threads of execution within the same program in a shared memory address space. They can also share open files and other resources. Threads enable concurrent programming and, on multiple processor systems, true parallelism.

To the Linux kernel, there is no concept of a thread. Linux implements all threads as standard processes. The Linux kernel does not provide any special scheduling semantics or data structures to represent threads. Instead, a thread is merely a process that shares certain resources with other processes. Each thread has appears to the kernel as a normal process and just happen to share resources, such as an address space, with other processes.

Kernel Threads #

It is often useful for the kernel to perform some operations in the background. The kernel accomplishes this via kernel threads, standard processes that exist solely in kernel-space. The significant difference between kernel threads and normal processes is that kernel threads do not have an address space. They operate only in kernel-space and do not context switch into user-space. Kernel threads, however, are schedulable and preemptable, the same as normal processes.

Kernel threads are created on system boot by other kernel threads. Indeed, a kernel thread can be created only by another kernel thread.

Process Termination #

When a process terminates, the kernel:

- Releases the resources owned by the process.

- Notifies the process’s parent of the termination of its child.

Generally, process destruction is self-induced. It occurs when the process calls the exit() system call. A process can also terminate involuntarily, this occurs when the process receives a signal or exception it cannot handle or ignore.

Upon deletion, the task enters the EXIT_ZOMBIE exit state. The only memory consumed is the one in the task list of the kernel. After the parent reap the child using the wait() system call, the kernel fully removes the task from the task list and the process is deleted.

Parentless Tasks, AKA Zombie Processes #

If a parent exits before its children, some mechanism must exist to reparent any child tasks to a new process, or else parentless terminated processes would forever remain zombies, wasting system memory. The solution is to reparent a task’s children on exit to either another process in the current thread group or, if that fails, the init process.

With the process successfully reparented, there is no risk of stray zombie processes. The init process routinely calls wait() on its children, cleaning up any zombies assigned to it.