System Calls #

In any modern operating system, the kernel provides a set of interfaces by which processes running in user-space can interact with the system. These interfaces give applications controlled access to hardware, a mechanism with which to create new processes and communicate with existing ones, and the capability to request other operating system resources. The existence of these interfaces, and the fact that applications are not free to directly do whatever they want, is key to providing a stable system.

Communicating with the Kernel #

System calls provide a layer between the hardware and user-space processes, which serves three primary purposes:

- Providing an abstracted hardware interface for userspace.

-

- For example, when reading or writing from a file, applications are not concerned with the type of disk, media, or even the type of filesystem on which the file resides.

- Ensuring system security and stability.

-

- The kernel acts as a middleman between system resources and user-space, so it can arbitrate access based on permissions, users, and other criteria. For example, this arbitration prevents applications from incorrectly using hardware, stealing other processes’ resources, or otherwise doing harm to the system.

- A single common layer between user-space and the rest of the system allows for the virtualized system provided to processes.

-

- It would be impossible to implement multitasking and virtual memory if applications were free to access access system resources without the kernel’s knowledge.

In Linux, system calls are the only means user-space has of interfacing with the kernel and the only legal entry point into the kernel other than exceptions and traps. Other interfaces, such as device files or /proc, are ultimately accessed via system calls. Interestingly, Linux implements far fewer system calls than most systems.

APIs, POSIX, and the C Library #

Applications are typically programmed against an Application Programming Interface (API) implemented in user-space, not directly to system calls, because no direct correlation is needed between the interfaces used by applications and the actual interface provided by the kernel. An API defines a set of programming interfaces used by applications. Those interfaces can be implemented as a system call, implemented through multiple system calls, or implemented without the use of system calls at all. The same API can exist on multiple systems and provide the same interface to applications while the implementation of the API itself can differ greatly from system to system.

The most common APIs in the Unix world is based on POSIX. Technically, POSIX is composed of a series of standards from the IEEE that aim to provide a portable operating system standard roughly based on Unix. Linux strives to be POSIX- and SUSv3-compliant where applicable.

On most Unix systems, the POSIX-defined API calls have a strong correlation to the system calls. Some systems that are rather un-Unix, such as Microsoft Windows, offer POSIX-compatible libraries.

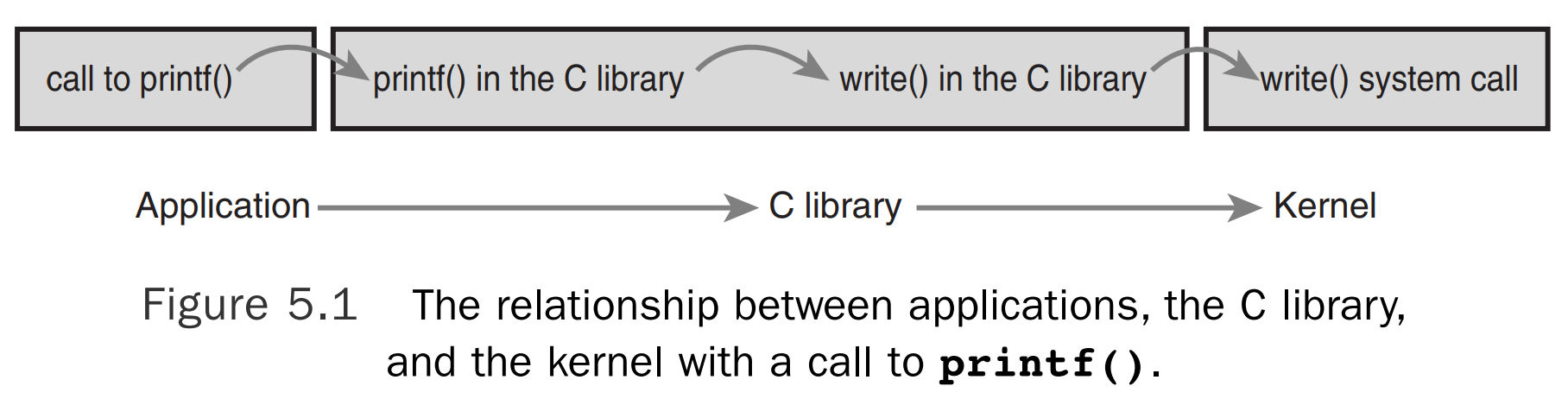

The system call interface in Linux, as with most Unix systems, is provided in part by the C library.

The C library implements the main API on Unix systems, including the standard C library and the system call interface. The C library is used by all C programs and, because of C’s nature, is easily wrapped by other programming languages for use in their programs. The C library additionally provides the majority of the POSIX API.

From the application programmer’s point of view, system calls are irrelevant; all the programmer is concerned with is the API. Conversely, the kernel is concerned only with the system calls; what library calls and applications make use of the system calls is not of the kernel’s concern. Nonetheless, it is important for the kernel to keep track of the potential uses of a system call and keep the system call as general and flexible as possible.

Syscalls #

System calls (often called syscalls in Linux) are typically accessed via function calls defined in the C library. The functions can define zero, one, or more arguments (inputs) and might result in one or more side effects. Although nearly all system calls have a side effect (that is, they result in some change of the system’s state), a few syscalls, such as getpid(), merely return some data from the kernel. System calls also provide a return value of type long (for compatibility with 64-bit architectures) that signifies success or error. Usually, although not always, a negative return value denotes an error. A return value of zero is usually (not always) a sign of success.

System Call Numbers #

In Linux, each system call is assigned a syscall number.This is a unique number that is used to reference a specific system call. When a user-space process executes a system call, the syscall number identifies which syscall was executed; the process does not refer to the syscall by name.

When assigned, the syscall number cannot change; otherwise, compiled applications will break. If a system call is removed, its system call number cannot be recycled, or previously compiled code would aim to invoke one system call but would in reality invoke another. Linux provides a “not implemented” system call, sys_ni_syscall(), which does nothing except return ENOSYS, the error corresponding to an invalid system call. This function is used to “plug the hole” in the rare event that a syscall is removed or otherwise made unavailable.

System Call Performance #

System calls in Linux are faster than in many other operating systems. This is partly because of Linux’s fast context switch times; entering and exiting the kernel is a streamlined and simple affair. The other factor is the simplicity of the system call handler and the individual system calls themselves.

System Call Handler #

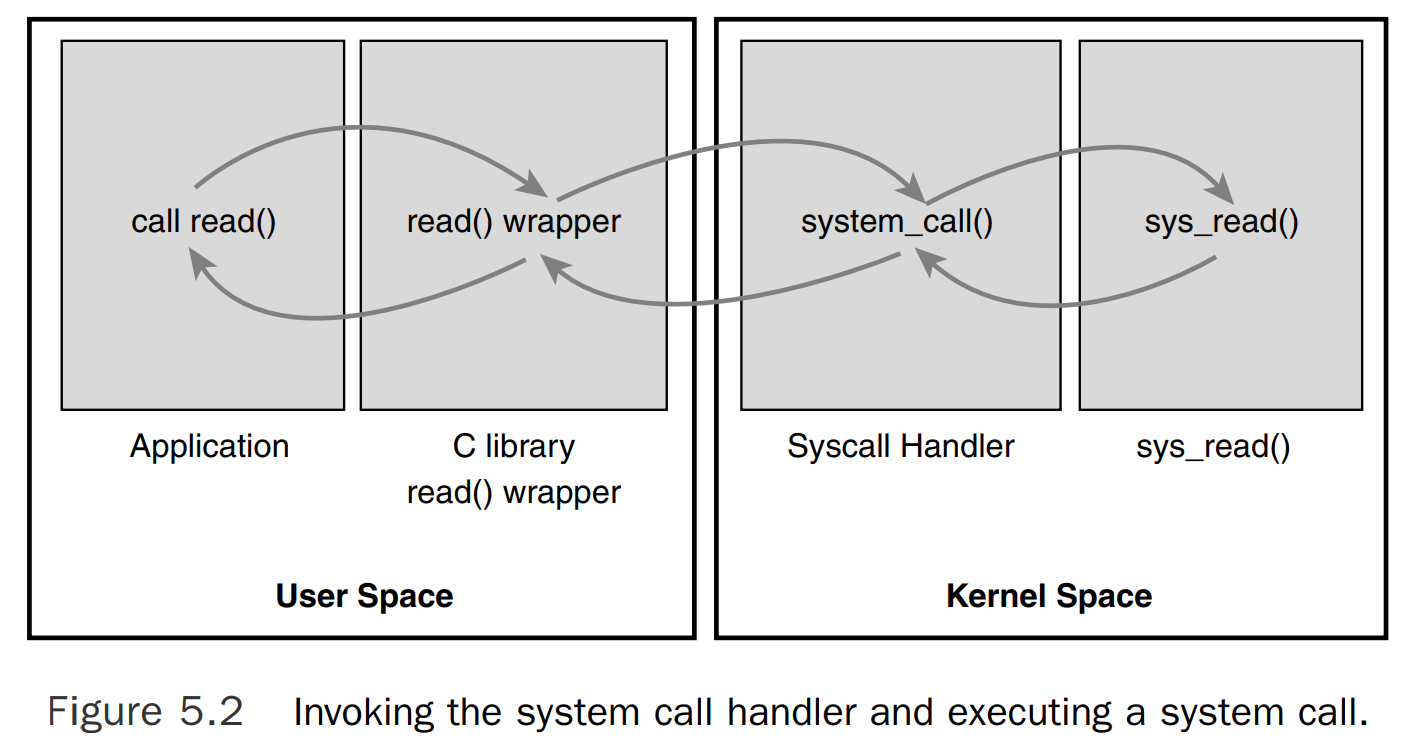

It is not possible for user-space applications to execute kernel code directly. They cannot simply make a function call to a method existing in kernel-space because the kernel exists in a protected memory space. If applications could directly read and write to the kernel’s address space, system security and stability would be nonexistent.

User-space applications signal the kernel that they want to execute a system call and have the system switch to kernel mode, where the system call can be executed in kernel-space by the kernel on behalf of the application. This mechanism is a software interrupt: incur an exception, and the system will switch to kernel mode and execute the exception handler. The exception handler in this case is actually the system call handler. The defined software interrupt on x86 for the syscall handler is interrupt number 128.

Recently, x86 processors added a feature known as sysenter, which provides a faster, more specialized way of trapping into a kernel to execute a system call than using the int interrupt instruction.

Denoting the Correct System Call #

Simply entering kernel-space alone is not sufficient because multiple system calls exist, all of which enter the kernel in the same manner.

Thus, the system call number must be passed into the kernel. On x86, the syscall number is fed to the kernel via the eax register.

Before causing the trap into the kernel, user-space sticks in eax the number corresponding to the desired system call. The system call handler then reads the value from eax.

Parameter Passing #

In addition to the system call number, most syscalls require that one or more parameters be passed to them. Somehow, user-space must relay the parameters to the kernel during the trap. The easiest way to do this is via the same means that the syscall number is passed: the parameters are stored in registers.

On x86-32, the registers ebx, ecx, edx, esi, and edi contain, in order, the first five arguments.

In the unlikely case of six or more arguments, a single register is used to hold a pointer to user-space where all the parameters are stored.

The return value is sent to user-space also via register. On x86, it is written into the eax register.

System Call Implementation #

The actual implementation of a system call in Linux does not need to be concerned with the behavior of the system call handler. Thus, adding a new system call to Linux is relatively easy. The hard work lies in designing and implementing the system call; registering it with the kernel is simple.

Implementing System Calls #

- Each syscall should have exactly one purpose. Multiplexing syscalls (a single system call that does wildly different things depending on a flag argument) is discouraged in Linux.

- System call should have a clean and simple interface with the smallest number of arguments possible.

- The semantics and behavior of a system call are important; they must not change, because existing applications will come to rely on them.

- Design the system call to be as general as possible with an eye toward the future. The purpose of the system call will remain constant but its uses may change.

Verifying the Parameters #

System calls must carefully verify all their parameters to ensure that they are valid, legal and correct to guarantee the system’s security and stability.

One of the most important checks is the validity of any pointers that the user provides. Before following a pointer into user-space, the system must ensure that:

- The pointer points to a region of memory in user-space. Processes must not be able to trick the kernel into reading data in kernel-space on their behalf.

- The pointer points to a region of memory in the process’s address space.The process must not be able to trick the kernel into reading someone else’s data.

- The process must not be able to bypass memory access restrictions. If reading, the memory is marked readable. If writing, the memory is marked writable. If executing, the memory is marked executable.

System Call Context #

The kernel is in process context during the execution of a system call. The current pointer points to the current task, which is the process that issued the syscall.

In process context, the kernel is capable of sleeping (for example, if the system call blocks on a call or explicitly calls schedule()) and is fully preemptible. The capability to sleep means that system calls can make use of the majority of the kernel’s functionality.